From the Crusades to Global Colonialism

Tracing the lineages of Western imperialism, European identity, and early capitalism in the process of Europe's expansion

Human history constitutes a massive, bafflingly complex, multi-dimensional tapestry, with each thread ultimately referring to all others. To view a given historical datum as a discrete unit, definitively circumscribed in time and space, is a perspective that is methodologically limited and not particularly fruitful for explanatory or interpretive purposes. To draw lessons and conclusions from history requires, above all, connections and context. With few historical phenomena is this as true as with the Crusades. To consider the Crusades as a distinctly medieval phenomenon, an outpouring of religious zeal and brutal violence incomprehensible to contemporary secular society, overlooks much of the phenomenon’s significance. Instead, to fully elucidate the meaning of that particular historical period, the Crusades must be located upon a wider global and temporal plane of continuity: as a key moment of early European expansion, presaging the Age of Discovery and the spread of Europe’s colonial empires across the world — the reverberations of this series of events echoing quite concretely down to the present day. Indeed, the ultimate failure of the Crusades, the inability of European Christendom to establish a long-term territorial presence in the Near East, marks a decisive historical turning point (represented most clearly by the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453): namely, the re-routing of Europe’s expansionist thrust from the Middle East and North Africa out across the Atlantic.

The character of this eventual expansion into the Western Hemisphere and, ultimately, East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, was shaped in large part by two key interrelated consequences of the Crusades. First, the creation of a crusading mentality, inseparable from the emergence of a broader European identity, which saw Western Christendom as confronting a monolithic bloc of enemies of the true faith—a perspective ultimately mutating into the concept of imperialist Europe as possessed of a unique civilizing mission. The second of these consequences was the decisive stimulus given by the Crusades to the emergence of a nascent merchant capitalism. Especially important in this respect was the opening of trade routes to the Near East in the wake of the campaigns to the Holy Land. The accumulation of merchant capital here was fueled by an intertwining of conquest and commerce, based on maritime adventurism and the control of key ports, with groups such as the Genoese or Venetians monopolizing the flows of valuable commodities such as spices or sugar.

Background: Feudal Europe and Expansion

The European ‘discovery’ of the Americas is often, rightly, seen as a dramatic world-historical break, the beginning of an age of Western global hegemony from which humanity is, perhaps, only now emerging. The Age of Discovery, however, was not just the starting point of a distinctive phase of European expansion—it was also the culmination and transformation of a prior one. This earlier period of European expansion, of which the Crusades were the most spectacular and intense exemplar, lasted from roughly 1000 AD through the fifteenth century, with a slowdown from the mid-fourteenth century caused by the bubonic plague. Retrospectively, the Turkish capture of Constantinople, the fall of Granada to the Spanish, and Columbus’ maiden voyage are all logical end-points of this cycle.1 Besides Holy Wars in the Middle East, North Africa, Iberia, and the Baltic, this outward thrust of Latin Europe also comprised Anglo-Norman campaigns in Ireland; pre-Crusade Norman expeditions in Southern Italy, Sicily, and the Byzantine Empire; German colonization throughout Central Europe; the establishment of Italian and Catalan maritime empires in the Mediterranean; and the early Iberian westward voyages to such areas as the Canary Islands and West Africa. This epoch also witnessed widespread internal growth throughout Latin Europe, as forest, fen, marsh, and moor were converted to cultivable land and myriad towns and villages were established.2

Certain scholars trace much of this Medieval European expansion to the activity of the post-Carolingian Frankish nobility. For the English historian Robert Bartlett, the aristocrats of the former Frankish Empire were perhaps the primary vectors of Latin Christian culture, carrying feudal social relations and Catholic ritual in their wake. He observes that by 1350 Latin Christendom possessed fifteen rulers with the title of king: of these, only three did not trace their descent back to noble houses of the former Frankish realms.3 The Marxist theorist Benno Teschke similarly emphasizes the importance of the post-Carolingian upper class to medieval European expansion. Teschke argues that “migrating Frankish lords, legitimated by the political Church, attempted to replicate their traditional forms of political reproduction in the extra-Frankish periphery. New feudal kingdoms sprang up headed by knights turned dynasts”.4

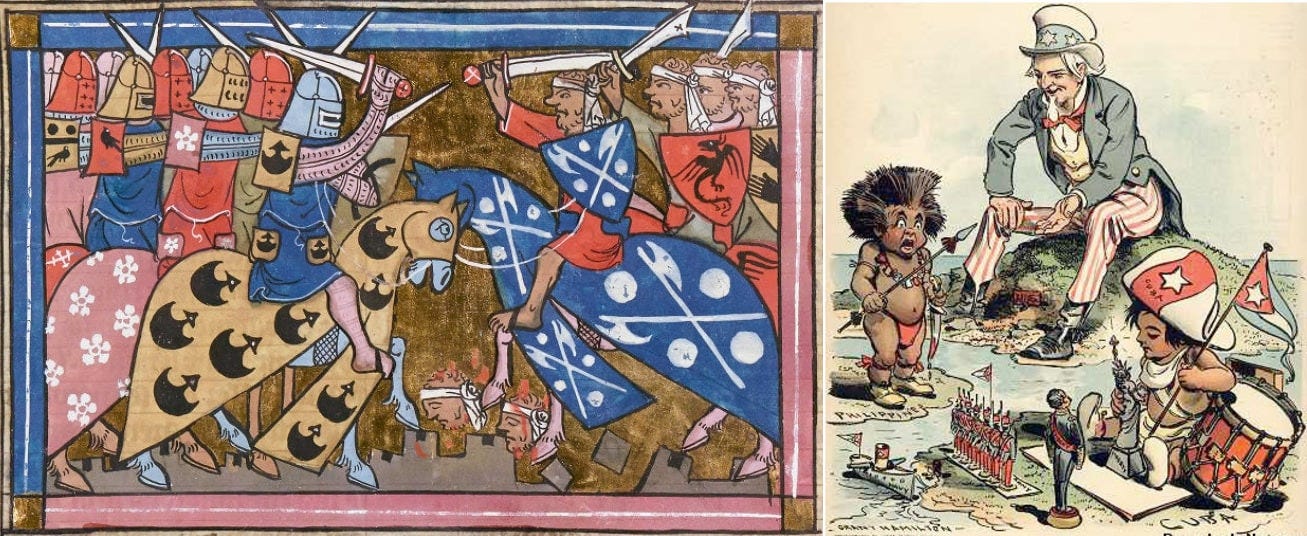

These new kingdoms were often a product of crusading expeditions: such was the case with the Latin principalities in the Levant, Portugal in formerly Muslim-ruled Iberia, and the so-called Latin Empire in Anatolia and Greece. Especially significant for Teschke in understanding this outward drive are the dynamics of Europe’s feudal social system. Like many other writers, he notes that feudalism contained a strong tendency toward expansion. In the deeply fragmented political sphere of feudalism, aristocratic power rested on the appropriation of agrarian surplus from a servile peasantry tied to the land. Intense intra-elite competition for land meant that there was always a strong incentive for European nobles, especially younger sons of that class’s middle and lower ranks, to seek their fortune through conquest abroad.5 The seminal speech by Pope Urban II launching the First Crusade reflected this centrifugal social context. As recorded by the writer Balderic of Dol, Urban lashed out at the bellicose nobility as “oppressors of children, plunderers of widows; you, guilty of homicide, of sacrilege, robbers of another's rights,” and urged them to turn their desire for plunder outward, against the Muslims in possession of the Holy Land.6

The Crusades and the Making of European Identity

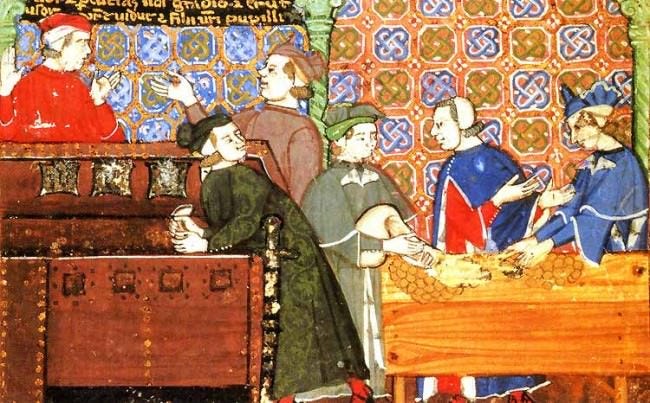

The Crusades represent a significant moment in the coalescence of the concept of Europe. Specifically, they helped to delineate Latin Christendom as a distinct cultural entity in opposition to both the Byzantine-centered Orthodox world and the sphere of Islam. Significant here was the Crusaders’ worldview of Western Christendom as confronted by a monolithic bloc of non-believers. This crusading mentality saw Latin Christendom as simultaneously under siege from implacably hostile forces and possessed of a unique mission which involved the defeat of such foes. Even after the ejection of the Crusaders from the Holy Land, this crusading spirit lived on—visible, for instance, in the actions of the early modern Iberians in the Americas who, influenced by their experiences in the recently completed Reconquista, viewed the non-Christian natives of the Western Hemisphere as ripe for conquest and conversion. The vision of a divinely guided mission against a world of enemies which was shared by the Crusaders and conquistadors was also apparent in the colonial efforts of the Protestant Dutch and English—one has only to think, for instance, of Puritan New England’s conception of itself as a ‘city on a hill’. Through its demarcation of a morally elevated Europe from a host of supposedly lesser peoples, the crusading mentality also influenced the later emergence of a virulent ideology of white supremacy and the related idea of an obligation on the part of imperial Europe to civilize more ‘primitive’ peoples. Even in more recent times, we can observe secularized nationalist versions of divine mission which echo the philosophy underlying the Crusades: from the German National Socialist idea of a drive to the East for lebensraum to contemporary notions of American exceptionalism which posit a US-led ‘free world’ confronted by authoritarian opponents.7

The Crusading Mentality in a Hostile World

Central to the crusading worldview’s contribution to European identity formation, then, was the contrast it assumed between Latin Christendom and a hostile bloc of ‘pagans’ and infidel. This idea recurs repeatedly in the literature and rhetoric of the Crusades. A key early example is embodied in the influential French epic poem The Song of Roland. This piece is an early landmark of French literature, representing a constitutive example of the genre known as the chanson de geste—a literary form focused on the heroic deeds of knightly warriors, instrumental in the emergence of the concept of chivalry. The poem centers in around a clash between a Carolingian army and a “horde of Saracens”, so numerous that the Frankish scout who sights them “cannot even add up the battalions—there are so many he loses count”.8 The poem constantly refers to Muslims as ‘pagans,’ said to worship not only Muhammad but a variety of other deities and demons including the Greek god Apollo.9 Similarly, the enemy army in the work’s final battle comprises not just Arabs but a whole host of far-flung peoples, some of whom even have “tufted bristles, just like hogs”, exemplifying quite clearly the monolithic range of enemies by which Latin Christendom felt menaced. In one small slice of the Muslim force, we encounter ten battalions, “The first is formed of ugly Canaanites…the next…of Turks…the third of Persians…the fourth…of Petchenegs”, and so on. Other groups included in the poem’s ‘pagan’ force include Avars, Huns, Armenians, Slavonians,” and “those from Occian Deserta…their skins…every bit as hard as iron.”10

While Latin Christendom primarily defined itself in opposition to Arab and Turkic Muslims during the Crusades, the campaigns also heightened its self-consciousness of difference compared to other groups, above all Europe’s Jews and the Orthodox Byzantines. Even though the latter were fellow Christians, the ideologists of the Crusades assimilated both groups to the category of enemies of the faith. Indeed, in the Fourth Crusade’s assault on Constantinople, the two were explicitly lumped together: the chronicler Robert de Clari noted how, in their sermon to the Latin army preceding the attack on the city, the Crusader clergymen validated the coming action by arguing that “the Greeks were traitors and murderers…worse than Jews.”11

Following the Iberian ‘discovery’ of the Western Hemisphere, Europe added the indigenous inhabitants of the Americas to the ranks of its infidel enemies. Especially interesting in this respect is the early 16th century Spanish chivalric epic Las Sergas de Esplandian (i.e., The Adventures of Esplandian) by Garci Rodriguez de Montalvo. The book displays the clear influence of the crusading ethos deeply embedded in Iberia due to the Reconquista, centering on the exploits of a fictional knight, Esplandian, who battles various mythological creatures before hastening to Constantinople to defend the city from a vast infidel army. The effect of the recently discovered New World on the transformation of the crusading mentality in the early modern period is clear in the work’s discussion of one of the leaders of the ‘pagan’ force, the warrior queen Calafia. In the book, Calafia rules “an island called California,” “east of the Indies,” a realm “populated by black women” who “lived in the fashion of Amazons.”12 The Amazon queen, despite an almost total lack of knowledge of Christendom, decides to join in the assault on Constantinople as, we are told, “the greater part of the world was moving in this onslaught against the Christians.”13 Here, then, is a clear reflection of Europe’s self-conception as a civilization confronted by a world filled with a range of hostile and barbarous forces. The inhabitants of the overseas realms recently encountered by Spain’s explorers are assimilated in the author’s imagination to Christendom’s Muslim nemeses by way of the names Calafia and California—these terms echoing, of course, the Arabic word caliph.

European Identity and the Term ‘Franks’

A notable indicator of the significance of the Crusades in the coalescence of a distinct European identity is the use of the term ‘Franks’ in discourse from the period. Both the Byzantines and Middle Eastern Muslims used the word to denote any group of Western Europeans. By the time of the Crusades, the adventurers and merchants of Latin Europe began to employ the term (even if they might be, e.g., English, Flemish, Norman, or German) when referring to themselves as a whole during their experiences in Iberia and the Eastern Mediterranean.14 Literary examples of such usage during the era of the Crusades abound: one such exemplar is the anonymously authored work De expugnatione Lyxbonensi which records an eyewitness account of the 1147 capture of Lisbon from its Muslim ruler by a heterogeneous crusading army composed of Portuguese, English, Flemings, Germans, Bretons, Scots, and French. When speaking of this polyglot mass as a unit, the author calls them all ‘Franks’. Furthermore, he details how the Portuguese King Afonso I did the same, speaking, for instance, of “the agreement between me and the Franks” promising the Crusaders land in the area of Lisbon in return for their help conquering the city.15

The use of ‘Franks’ as a phrase signifying Western Europeans during the Crusades was especially crucial in terms of identity formation in that it was not explicitly related to religion. It thus marks an important intermediate step on the journey from the idea of Christendom to that of the secular community of Europe. The term thus prefigures later modern perspectives assuming a shared ethnic or racial background (as opposed to a religious or a linguistic one, e.g., the use of Latin for sacred, literary, or administrative purposes) among Europeans on a biological or genetic basis. Its emergence thus demonstrates the importance of the Crusades and the influence of the crusading mindset on conceptions of European identity. Such an identity was a necessary precondition for the crystallization of notions of an imperial civilizing mission carried by Europe, a perspective which itself echoes the Crusaders’ vision of themselves as a force enacting the divine will to conquer the Holy Land.

The Crusades and the Emergence of Merchant Capitalism

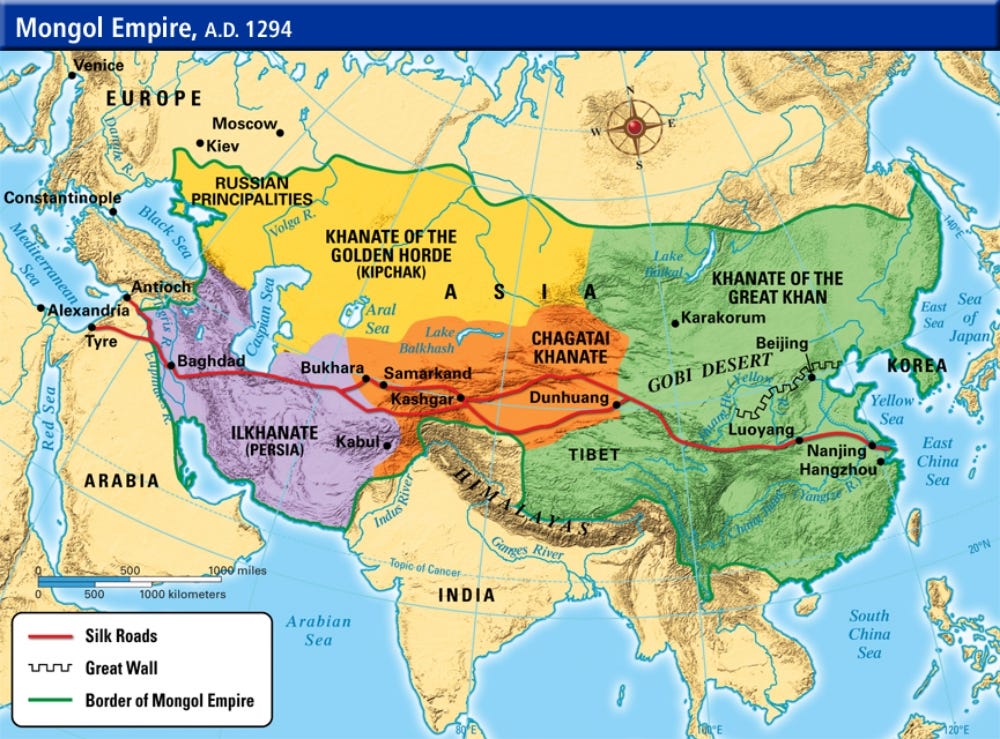

The English historian Michael Postan notes “The idea that the crusades were a turning point in the history of European economy is one of the most cherished notions of economic history”. Postan, however, questions whether “their consequence was to augment the flow of gold…to the continent of Europe, or…to drain the continent of its precious metals.”16 What is important for our present purposes, though, is not so much the question of whether the Crusades led to a quantitative increase in total European wealth. Instead, in understanding the bearing of the Crusades on later European expansion, what is critical are the campaigns’ broad structural economic effects. On this level, one of the most significant consequences of the Crusades was their salutary impact on commercial activity. Specifically, the Crusades provided a stimulus to the crystallization of wide-ranging circuits of European merchant capital. Out of these emerged a full-fledged merchant capitalism which, in the early modern era, underlay much of European colonialism. Eventually, this merchant capitalism helped lay the groundwork for the Industrial Revolution and subsequent metastasis of capitalist social relations across the globe, creating the world we know today. For reasons of space, though, a comprehensive analysis of the relationship between the Crusades and the emergence of merchant capitalism is beyond the scope of the present piece: instead, we will briefly examine some of the most significant aspects of this phenomenon.

The Crusades, Trade Networks, and the Thirteenth Century World-System

The Crusades played a notable part in sparking what some scholars term the Commercial Revolution, issuing in what Janet Abu-Lughod calls the ‘Thirteenth Century World System.’17 Abu-Lughod sees this world-system as a coherent, if segmented, whole, extending from the Mediterranean to the South China Sea.18 Indeed, she argues that “although the Crusades eventually failed, they had a significant consequence. They were the mechanism that reintegrated northwestern Europe into a world system.”19 This integration of European and Middle Eastern circuits of trade represented perhaps the most important economic consequence of the Crusades. From thereon, the eyes of many European merchants and explorers were oriented outward. When, ultimately, they found their paths into the Near East and North Africa largely blocked by the Ottomans, they set their sights westward, pioneering new paths to West Africa, Asia, and the Americas.

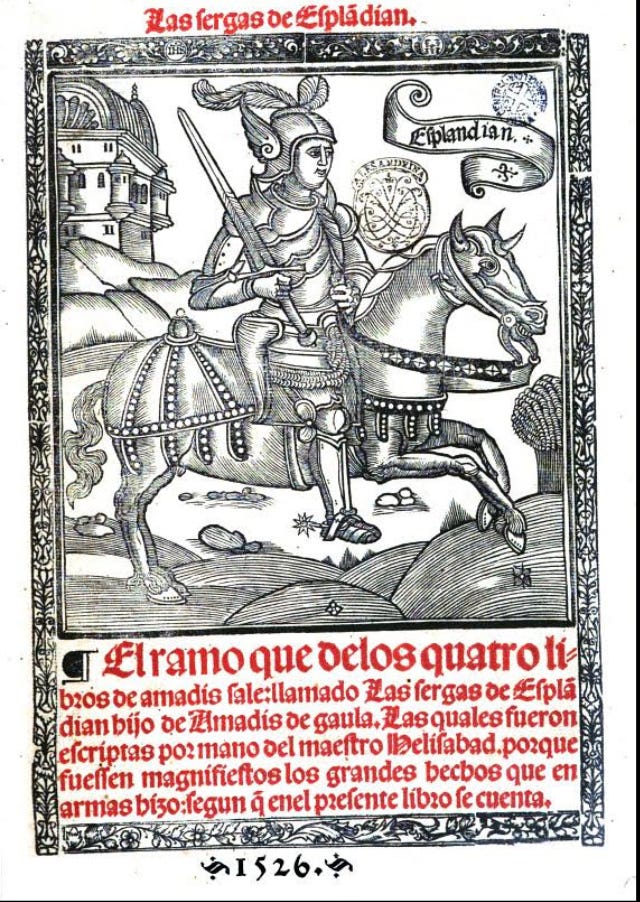

This broadening of European horizons during the Crusades benefited from the creation of what some writers have dubbed a pax Mongolica. The Mongol conquests during the thirteenth century meant that a single sociopolitical framework stretched from China to Syria (even if the Mongol realm quickly divided into several competing kingdoms ruled by Genghis Khan’s descendants). This absorption of much of the Eurasian landmass under Mongol rule facilitated overland trade across Asia as caravan routes traversing the continent flourished. This was the world which medieval European merchants such as the famous Venetian Marco Polo entered in search of fortune. The details of this period’s wide-ranging Eurasian trade networks survive in documents such as Polo’s account of his travels. Therein he describes important commercial cities such as Ayas in Cilician Armenia, where he began his long journey to Mongol-ruled China, and which served as a key entrepot for trade between Europe and the Mongol realms. According to the Italian businessman, Ayas (which he refers to as Layas) is where “all the spicery, and the cloths of silk and gold, and the other valuable wares that come from the interior, are brought.” As such, “the merchants of Venice and Genoa, and other countries, come thither to sell their goods, and to buy what they lack.”20

The thirteenth century world-system theorized by Abu-Lughod and recorded first-hand by Marco Polo began to fracture with the disintegration of the Pax Mongolica and the spread of bubonic plague along the networks traversed by its merchants.21 By the fifteenth century, direct access by Europeans to the trade routes of the East was relatively limited: the fall of the Crusader states, the rise of the Egyptian Mamluks, and the wide-ranging conquests of the Ottoman Turks all contributed to diminish the power of European merchants in the Middle East and beyond. Despite this, the Venetians in particular managed to retain their role as purveyors of silk, cotton, sugar, and spices from Asia to Europe. The desire to find an alternative route to Asia, bypassing the Venetians, Mamluks, and Turks, was an important motivating factor in the wide-ranging voyages of discovery which set off from Portugal throughout the fifteenth century.22 With expansion largely blocked into the Middle East and North Africa, other European powers eventually followed the lead of the Portuguese, ultimately establishing vast colonial empires from which Europe siphoned a wide variety of valuable commodities.

Italian Merchant Capital and the Foundations of European Colonization

Perhaps the main beneficiaries of the Crusades were not the ephemeral Latin principalities in the Levant but the city-states of Italy, above all Genoa and Venice. These Italian city-states were also some of the most crucial entities in terms of the transition between Europe’s medieval expansion, exemplified by the Crusades, and its later waves of colonization into the Americas, Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa.

While the cities of Italy started their political and economic ascent before the Crusades began, the campaigns to the Holy Land accelerated their rise: by the time the Crusaders were ejected from the Levant in 1291, both Venice and Genoa had constructed prosperous, far-flung maritime empires. The benefits the Italians derived from the Crusades were complex and multi-layered. For starters, shipowners in Italy and elsewhere did a brisk business in transporting Crusaders and associated pilgrims to the Holy Land.23 Secondly, from the very beginning of the Crusades, the Italians participated in the campaigns themselves and, as such, “demanded as a reward for their crucial help trading compounds and special privileges in the cities…under Crusader control.” The Genoese, for instance, received “one third of the cities of Acre, Arsuf, Beirut, Caesarea, and Tripoli”, while the Venetians and Pisans were awarded similar status in a number of towns.24 On top of these concessions, the Italians, like their Crusader allies, engaged in widespread plundering throughout the Near East during the campaigns of Holy War. Perhaps the most egregious example of such looting occurred during the 1204 sack of Constantinople by the Venetians and their Crusader allies in the course of the Fourth Crusade. The Byzantine chronicler Nicetas Choniates described the orgy of pillaging perpetrated by the Latin forces, lamenting how they “snatched the precious reliquaries, thrust into their bosoms the ornaments which these contained, and used the broken remnants for pans and drinking cups”, leaving “no place…unassailed.”25

The Crusades, then, represented a boon for the Italian city-states. The period also witnessed the construction by both Venice and Genoa of wealthy maritime empires, based in part on trade connections with the Middle East that the Crusades opened up. It was in these Italian empires that much of the infrastructure employed by European colonialism in the early modern period was first forged. Many of the innovations in naval technology employed by European voyages during the Age of Discovery were first disseminated to Europe through trade routes to the Middle East frequented by Italian traders: such was likely the case with the compass, the spherical astrolabe, and the portolan.26 Similarly, a number of the socioeconomic forms which characterized later European colonial empires were also evident in the Italian-ruled realms. Two key examples are the slave-worked plantation and the chartered company.

The kind of slave-employing plantations later perfected by the European powers in Brazil, Haiti, Cuba, and the Southeastern US first began as organizational means to further the production of sugar as a commodity for export. By the time the Crusaders arrived in the Holy Land, sugar cane had been grown as a cash crop in the Middle East, sometimes using slave labor, for centuries. Shortly after the establishment of the Crusader states, Western Europeans began growing their own sugar in the region.27 In his book The Beginnings of Modern Colonization, the historian Charles Verlinden traces the emergence of plantation slavery and its spread from the Eastern Mediterranean out across the Atlantic as a process fueled in large part by Italian investment in sugar production. Venetian merchants and landowners held plantations around Tyre, on Cyprus, and Crete, the latter island an important hub in the Mediterranean slave trade.28 These late Medieval slaves were largely Greeks, Tatars, Arabs, Slavs, and various peoples from the Caucusus — Italian shippers transported them to their ultimate destinations from centers of the slave trade such as the Black Sea hinterland.29 By the fifteenth century, sugar plantations “had spread from the Eastern Mediterranean to the shores of the Atlantic.” Especially crucial in the product’s introduction to this latter area, according to Verlinden, were Genoese investors, “whose capital…stimulated production in the Madeiras, a Portuguese colony, and the Canary Islands, a Spanish possession.”30 Following the Iberian voyages to the New World, sugar plantations spread into the Western Hemisphere — and ultimately plantation slavery, taking on a particularly brutal form, would be used there to produce a variety of other commodities such as cotton, tobacco, coffee, and indigo.

Another economic technique crucial in the colonial projects of early modern Europe was the chartered company. These were entities composed of shareholders or investors endowed with a government charter (in a monarchy, granted by the king) awarding them special rights regarding commerce and colonization. Verlinden argues for “a direct line of development between…the mahonas or colonial Genoese companies of the fourteenth century…and the Spanish and Portuguese organizations…and the Dutch, French and English companies which directed the colonial expansion of those nations.”31 The relationship between the mercantile concerns of the Italian city-states and the later Iberian, Dutch, English, and French companies was characterized not only by morphological continuity but even, in some cases, by direct connections on the individual level. Sebastian Cabot, son of the famous explorer John Cabot, was a member of an old Italian merchant family who became one of the chief organizers of the English Muscovy Company. Verlinden credits the Muscovy Company’s introduction of the concept of the joint-stock company (i.e., a firm held jointly by shareholders who may buy and sell its stock) to England as “attributable to the experience acquired by Cabot in Italy and Spain,” regions where the joint-stock form “had existed for some time.”32 Similar companies, such as the Dutch East India Company or its later British counterpart, would play a major role in the maturation of a global commercial capitalism, laying the foundations for the present-day economic domination of massive multinational conglomerates.

Conclusion

As foreign as they may seem to individuals in the relatively secular contemporary West, it is perhaps impossible to adequately understand the making of the modern world without appreciating the consequences of the Crusades. As we have seen, two such consequences were especially important in laying the groundwork for the later global imperial expansion of Europe which created the world as we know it today. The first of these was the emergence of an aggressive crusading mentality among the European upper classes. This ideological development was crucial in the broader constitution of a distinctive European identity, forged in large part through conflict with Middle Eastern Muslims and Orthodox Byzantines. Following the ‘discovery’ of the New World by Iberian powers strongly influenced by the ethos of Holy War which characterized the Reconquista, the crusading mindset began to mutate into a sense of imperial mission on the part of a morally elevated Europe. This colonialist ideology helped legitimize the occupation of much of the globe by Europe’s imperial powers, somewhere along the way giving birth to the concept of American exceptionalism which continues to shape global politics today. The second crucial consequence of the Crusades was the stimulus the campaigns provided to the crystallization of prosperous and productive circuits of European merchant capital. It was this nascent merchant capitalism that would fuel much of European colonialism during the early modern period. Ultimately, these capital networks created some of the necessary preconditions for the Industrial Revolution, thus fueling the global spread of capitalist social relations. As far removed temporally and culturally the Crusades may seem, then, they nevertheless had a clear bearing on the development of two massive, intensely complex forces which deeply structure life as we experience it today: Western imperialism and global capitalism.

Archibald R. Lewis, “The Closing of the Mediaeval Frontier 1250-1350.” Speculum 33, no. 4 (1958): 475–83. Note that Lewis argues this first wave of expansion ended around the mid-14th century.

Fernand Braudel, The Perspective of the World: Civilization and Capitalism 15th-18th Century Volume III, trans. Sian Reynolds (London: Collins, 1984), 92-3.

Robert Bartlett, The Making of Europe: Conquest, Colonization, and Cultural Change 950-1350 (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1993), 40-2.

Benno Teschke, The Myth of 1648: Class, Geopolitics, and the Making of Modern International Relations (London: Verso, 2011), 111-12.

Teschke, Myth of 1648, 84-99.

Paul Halsall, “Medieval Sourcebook: Urban II (1088-1099): Speech at Council of Clermont, 1095, Five Versions of the Speech,” Internet history sourcebooks project, December 1997, https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/source/urban2-5vers.asp#gesta.

Note, in this context, the pro-Nazi German theorist Carl Schmitt’s discussion of the nation-state as characterized by secularized theological concepts, what he terms ‘political theology’—see Carl Schmitt, Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty, trans. George Schwab (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 2008), 36-42.

Robert L. Harrison, tran., The Song of Roland (New York, NY: Signet Classic, 2012), 86.

See, for instance, Harrison, Song of Roland, 135 and 166.

Harrison, 156-8.

Paul Halsall, “Medieval Sourcebook: Robert de Clari: The Capture of Constantinople”, Internet history sourcebooks project, December 1997, https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/source/clari1.asp.

Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo, The Chronicles of California's Queen Calafia: Retold from Garci Rodriguez De Montalvo's 1587 Castilian Edition of Amadis, Book 5, the Adventures of Esplandian, ed. Mozelle Sukut, trans. Constance Kihyet (San Juan Capistrano, CA: Trails of Discovery, 2007), 17.

De Montalvo, California’s Queen Calafia, 21.

Bartlett, Making of Europe, 103.

Charles Wendell David, tran., De Expugnatione Lyxbonensi: The Conquest of Lisbon (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001), 110.

M. Postan and E. E. Rich, The Cambridge Economic History of Europe Volume II: Trade and Industry in the Middle Ages (Cambridge: University Press, 1952), 163.

Janet Abu-Lughod, Before European Hegemony: The World System A.D. 1250-1350 (Oxford University Press, 1989), 8-9.

Abu-Lughod, Before European Hegemony, 33.

Abu-Lughod, 47.

Marco Polo, The Travels of Marco Polo: The Complete Yule-Cordier Edition Volume I, ed. Henri Cordier, trans. Henry Yule (New York: Dover Publications, 1993), 23.

Abu-Lughod, 170-5.

Pierre Chaunu, European Expansion in the Later Middle Ages (Amsterdam: North-Holland, 1979), 63.

Postan and Rich, Cambridge Economic History of Europe, 332.

Gerald W. Day, “The Impact of the Third Crusade upon Trade with the Levant”, The International History Review 3, no. 2 (1981): 161.

Paul Halsall, “Medieval Sourcebook: Nicetas Choniates: The Sack of Constantinople (1204)”, Internet History Sourcebooks Project, May 1996, https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/source/choniates1.asp.

Chaunu, European Expansion, 70-3.

Charles Verlinden, The Beginnings of Modern Colonization (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1970), 18.

Verlinden, Beginnings of Modern Colonization, 21.

Verlinden, 28-32.

Verlinden, 22.

Verlinden, 7.

Verlinden, 8.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

David, Charles, trans. De Expugnatione Lyxbonensi: The Conquest of Lisbon. New York: Columbia University Press, 2001.

de Montalvo, Garci Rodriguez. The Chronicles of California's Queen Calafia: Retold from Garci Rodriguez De Montalvo's 1587 Castilian Edition of Amadis, Book 5, the Adventures of Esplandian, Chapter 157 Illustrated with Woodcuts from French Editions of Amadis De Gaule, Published between 1548 and 1555. Edited by Mozelle Sukut. Translated by Constance Kihyet. San Juan Capistrano, CA: Trails of Discovery, 2007.

Halsall, Paul. “Medieval Sourcebook: Nicetas Choniates: The Sack of Constantinople (1204).” Internet history sourcebooks project, March 1996. https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/source/choniates1.asp.

Halsall, Paul. “Medieval Sourcebook: Urban II (1088-1099): Speech at Council of Clermont, 1095, Five Versions of the Speech.” Internet history sourcebooks project, December 1997. https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/source/urban2-5vers.asp#gesta.

Harrison, Robert L., trans. The Song of Roland. New York, NY: Signet Classic, 2012.

Polo, Marco. The Travels of Marco Polo: The Complete Yule-Cordier Edition Volume I. Edited by Henri Cordier. Translated by Henry Yule. New York: Dover Publications, 1993.

Secondary Works

Abu-Lughod, Janet L. Before European Hegemony: The World System A.D. 1250-1350. Oxford University Press, 1989.

Bartlett, Robert. The Making of Europe: Conquest, Colonization and Cultural Change 950-1350. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015.

Braudel, Fernand. The Perspective of the World: Capitalism and Civilization 15th-18th Century Volume III. Translated by Sian Reynolds. London: Collins, 1984.

Chaunu, Pierre. European Expansion in the Later Middle Ages. Amsterdam: North-Holland, 1979.

Day, Gerald W. “The Impact of the Third Crusade upon Trade with the Levant.” The International History Review 3, no. 2 (1981): 159–68. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40105123.

Lewis, Archibald R. “The Closing of the Mediaeval Frontier 1250-1350.” Speculum 33, no. 4 (1958): 475–83. https://doi.org/10.2307/2846901.

Postan, M., and E. E. Rich. The Cambridge Economic History of Europe Volume II: Trade and Industry in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: University Press, 1952.

Schmitt, Carl. Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty. Translated by George Schwab. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 2008.

Teschke, Benno. The Myth of 1648: Class, Geopolitics, and the Making of Modern International Relations. London: Verso, 2011.

Verlinden, Charles. The Beginnings of Modern Colonization. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1970.